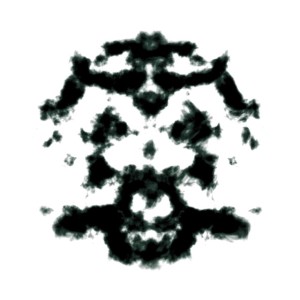

The famous Roschach test is probably the most famous psychological test. Patients are shown random images of inkblots and asked to talk through what they see. In the case of this test, it is not really important what the ink blots show, but rather what people see within them. While there have been some criticisms of the technique over the years, it continues to be widely used based on the amount of information that people share as they link into randomness and are asked to see patterns. Recently, when working through an initially elusive problem, we came to realize just how powerful this dynamic is within people as we identified a problem solving anti-pattern we dubbed “Rorschach problem solving”, where people look at the presenting evidence of a problem and project onto it their own biases.

The famous Roschach test is probably the most famous psychological test. Patients are shown random images of inkblots and asked to talk through what they see. In the case of this test, it is not really important what the ink blots show, but rather what people see within them. While there have been some criticisms of the technique over the years, it continues to be widely used based on the amount of information that people share as they link into randomness and are asked to see patterns. Recently, when working through an initially elusive problem, we came to realize just how powerful this dynamic is within people as we identified a problem solving anti-pattern we dubbed “Rorschach problem solving”, where people look at the presenting evidence of a problem and project onto it their own biases.

Symptoms of a Broken Problem Solving Approach

Ideally, when presented with a series of data points but no known root cause, we consider the possibilities, develop theories, and seek to disprove or confirm them. Models similar to this – the Scientific Method being the best known one – go back as far as the Egyptians with their empirical observations with astronomy, mathematics and medicine. Unfortunately, this continues to be an ideal that we don’t always achieve. There too many to name, but here are some of the most common ways we are betrayed by our own minds.

- Fundamental Attribution Bias – when we place too much emphasis on motive or competency of individual actors as opposed to situational factors. When trying to diagnose a problem, this frequently manifests in a game of blame where the root cause is pinned on a specific individuals or groups because they “alway mess up”, “don’t care”, or some other similarly judgmental assessment.

- Accessibility Bias – when people focus on one specific option because it is more well known to them than others. This particular bias can be a great asset or liability depending on how it is managed within a group of people coming from different backgrounds, as their prior history will make different ideas and concepts more accessible, hence they will be more likely to diverge on conclusions from the same set of initial facts.

- Anchoring – the phenomena where people start at the first idea, or quantity, proposed and then adjust based on that. Beginning from an initial starting point, people will be anchored towards it. For example, someone estimating the price of a product who is given a number obviously higher than is correct will most likely provide a response that is lower than the proposed weight, but may be higher than what they would have said if they weren’t given any prior information. This explains why you always see the high sticker price when buying a car, as that is to anchor you to a higher point from which you then negotiate down, as opposed to determining a fair value and then negotiating from that point. In when problem solving, it is likely that an initial set of ideas will be proposed, and if teams are not careful, they can easily become anchored to those, preventing them from moving on to considering new theories.

- Confirmation Bias – the natural motivation of most people is to seek to prove what they believe, rather than to disprove it. This frequently leads to a massive blind spot as people search for, and therefore see only, confirming information. This is the primary reason why the default hypothesis in scientific experiments is the null hypothesis, that the hypothesis is wrong and thus experiments are designed to disprove it. In the case of problem solving, it means that we fail to consider all the data, and once we have our initial idea, most probably driven through the accessibility bias, we seek to simply prove that, rather than consider all the possible data or ways to explore the situation.

- Frequency Illusion – the perceived experience where once you start to look for something, you see it everywhere, creating the experience that thing has increased in frequency. The non-technical example most people have experienced is that once they purchase a new type of car, they see that model everywhere. The frequency of that car most likely didn’t change, just the person’s awareness of it. Likewise when troubleshooting a technical problem, we frequently begin to start watching things much closer and become much more aware about small errors, inconsistencies and other strange patterns. We probably didn’t have a great understanding of whether or not these were occurring before the problem manifest, but now we are noticing them all over the place and it can become easy to make a correlation where one does not exist.

This is not a comprehensive list, but they nicely demonstrate some of the mental shortcuts our brains will make if we are not aware of it. Ultimately it is that unawareness that leads us to the concept of the Rorschach problem solving approach, where we learn more about the people and what they already believed than we do about the actual problem. The cognitive biases above show how a group, especially of like minded people, can enter a negatively reinforced loop whereby they jump to a conclusion, based on their own experiences and biases, and then simply reinforce that more and more regardless of if it is truly making a difference.

Breaking out of the Loop

In the case of the example I alluded to in the beginning, we were able to spot this dynamic precisely because we came from different teams with different technical backgrounds. Like so many things, merely naming it helped us overcome it. We began to talk about our own thought patterns and how we got to the conclusions we did, as well as where we may have been making inferences that were not justified. To take our list of biases, here would be some good questions you can use that help deconstruct such a situation

- What biases may I be bringing about the group / technology / people who are involved in this issue? If the person involved was someone I completely trusted – or even me – how would I address the situation differently? (Fundamental Attribution Bias)

- What information or technical areas am I most likely to look to when solving a problem? What areas might be potentially risky, but less obvious or common to me? (Accessibility Bias)

- Before we dug into this, what idea was initially hypothesized as the problem? How has that impacted our searching to so far? What other initial positions might have sent us in a different direction. (Anchoring)

- If I had to disprove my current theory, how would I go about picking it apart? If I were advising someone else to argue against this, how would I help them show it was wrong? (Confirmation bias)

- How can I show that an indicator which appears to have increased recently really did or that we simply weren’t watching it closely prior? (Frequency illusion)

Don’t Swim Alone and Be Methodical

Like in so many things, one of the best ways to confront these challenges is to make sure you never do it alone and that ideally you are doing with people who have different backgrounds and perspectives so as to ensure you are not all similarly blinded by the same preconceived notions. I’ve additionally found it very useful to have a simple routine you may use when going through things like this. It could be no more than methodically naming theories – being sure to call them just theories – and then identifying how to test each one. Building habits can be quite important as most the research on human behaviors shows that when we are under stress, tired, or feeling threatened, we are more likely to fall back to habits and routinized behaviors. Unless you’ve built questions and processes like the ones just discussed into ingrained muscle memory, then chances are when you are under pressure trying to solve a time sensitive problem, you may find yourself swearing you see a rabbit in the ink blot, rather than making solid progress confronting the challenge before you.